DJB

Last Tuesday evening I was among an audience of around fifty to sixty at Columbia University in New York to see Saipulla Mutallip’s new documentary film, Qarangghu Tagh. Following a Q&A with the director we also watched his short feature, Bogha, which is an adaptation of a story by the Uyghur author Mämtimin Hoshur. Both films are really well made–anyone who has the chance to see either of them should do so. Independent documentaries from Xinjiang are practically unheard of: Qarangghu Tagh may well be the very first of its kind. And it’s not just ground-breaking in that respect: it’s shot in a part of Xinjiang that no-one watching the film is ever likely to be able to visit themselves. I can’t emphasise enough how lucky we are that Saipulla managed to get his camera up the treacherous roads and bring back his impressions of the place for us.

Here’s a trailer for Qarangghu Tagh:

Qarangghu Tagh is the name of the village that features in Saipulla’s film. The name just means “Dark Mountain,” though in English the film has been given the title The Villages Afar. It’s a small village set in the steep mountains to the south of Khotan, and as you can see from the clip above, it’s a remote place by anyone’s standards. The red dot on this map shows roughly where it is:

Filmed in the course of a number of visits between 2009 and 2012, Qarangghu Tagh centres around local memories of a massacre that took place there in the 1930s. There’s a song about the event, which an old man strumming a rawap sings at various points in the film, and the song seems to set the terms for the way most people “remember” the incident. Of course, that’s not all the film is about: during the interviews, we learn a lot about life in the village, its connection to surrounding communities, and to the state. At the film’s conclusion, the focus turns to the local school, and the experiences of the few children who have had the chance to study in Xinjiang’s capital of Ürümchi.

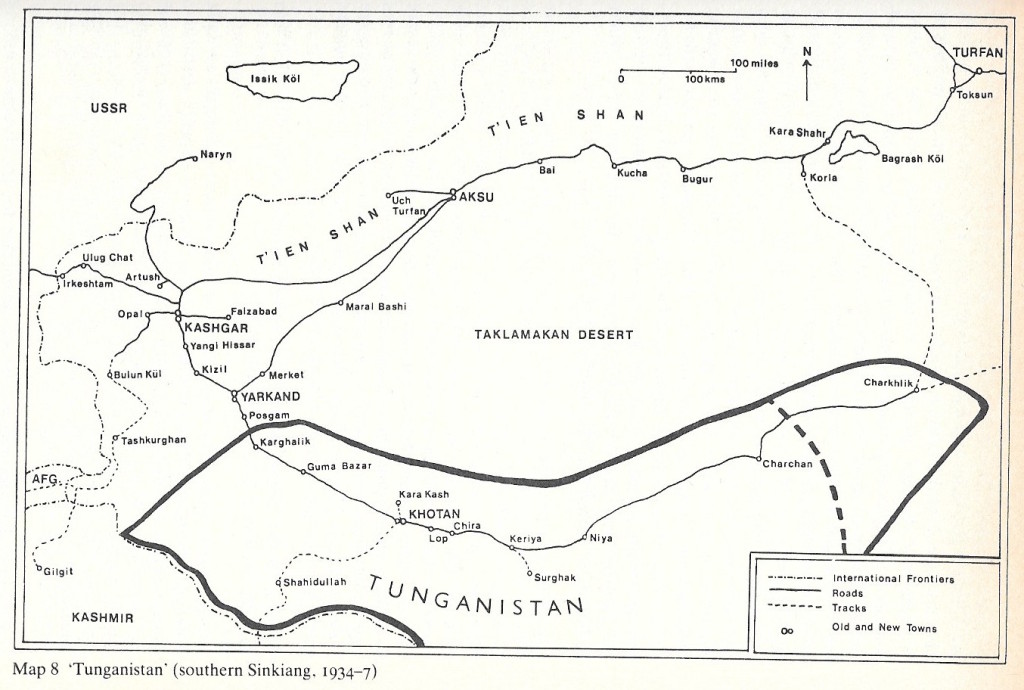

The massacre in question must have occurred some time between 1934 and 1937, while troops loyal to the Dungan (i.e. Hui 回, Chinese-speaking Muslim) officer Ma Hushan 馬虎山 were in control of the Khotan oasis and its surrounds. These soldiers were the remnants of the Nationalist Army’s 36th Division, who had been led into Xinjiang from Gansu by the teenage generalissimo Ma Zhongying 馬中英. Repelled from the provincial capital Ürümchi, in early 1934 Ma Zhongying led his troops south to Kashgar, where they toppled the short-lived East Turkistan Republic. Ma then met with Soviet officials at the border, and mysteriously disappeared into the Soviet Union. (The mystery is gradually being cleared up on the basis of Soviet archives–a few relevant documents can be found here at the Wilson Center’s digital archive).

With the blessing of the Soviets, provincial troops soon occupied Kashgar, obliging Ma Zhongying’s second-in-command Ma Hushan to lead his men further south to Khotan. There they set up a regime that while nominally still loyal to Nanjing, was essentially independent. Foreign travellers passing through (most notably the travel writers Peter Fleming and Ella Maillart) christened Ma Hushan’s mini-state “Dunganistan” or “Tunganistan” (the word Dungan is often spelt “Tungan”). This website purports to show us the flag of Tunganistan, a white crescent-moon and star on a red background. And here’s a map of Tunganistan from Andrew Forbes’s Warlords and Muslims (1986):

This was obviously a violent period throughout Xinjiang, but for some reason this tucked-away mountain village was the scene of particular horrors in the mid-1930s. As we gradually learn in the course of the film, Ma Hushan’s troops (Dungans, but probably also including Uyghurs), fell upon the village at prayer-time, dragging all men of fighting age from the village mosque. They executed around ninety on the spot, and took four back with them to meet the same fate in Khotan. No one in the film has a particularly good explanation for why they did this. There’s a curious line in the folksong about a “king” (padsha) coming out of the mountains: some of the elderly villagers that Saipulla interviewed think that the emergence of this self-styled “king” was the reason for the Dungan attack; others dismiss this idea, convinced that backward mountain-folk such as themselves could never produce a king. It’s all very intriguing, enough to keep the viewer in suspense to the end.

I hadn’t heard of Qarangghu Tagh before Saipulla’s film, so watching it led me to dig around a bit to see what can be found out about the place. Sources on “Tunganistan” are notoriously scarce, but earlier accounts of Qarangghu Tagh give some clues as to what was going on there in the 1930s.

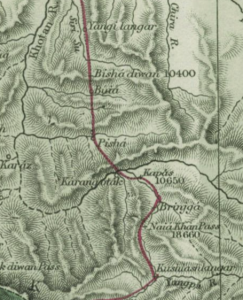

These days, the main highway linking what was once British India with Xinjiang runs through the Sarikol Valley and descends via the village of Opal to Kashgar. Other routes used to be more popular though: a lot of travel accounts describe the trip from Ladakh in north India to Yarkand. There were also possible itineraries leading from Ladakh to Khotan, and Qarangghu Tagh seems to have sat along one such route. In the 1860s, the British colonial surveyor William Johnson visited Khotan at the invitation of Habibullah Khan, who had recently wrested it from Qing control at the head of a local rebellion. You can see Qarangghu Tagh on Johnson’s map:

Johnson made note of the fact that Qarangghu Tagh (he calls it Kárangoták) was a place of exile for criminals, and gives the following brief description:

Johnson made note of the fact that Qarangghu Tagh (he calls it Kárangoták) was a place of exile for criminals, and gives the following brief description:

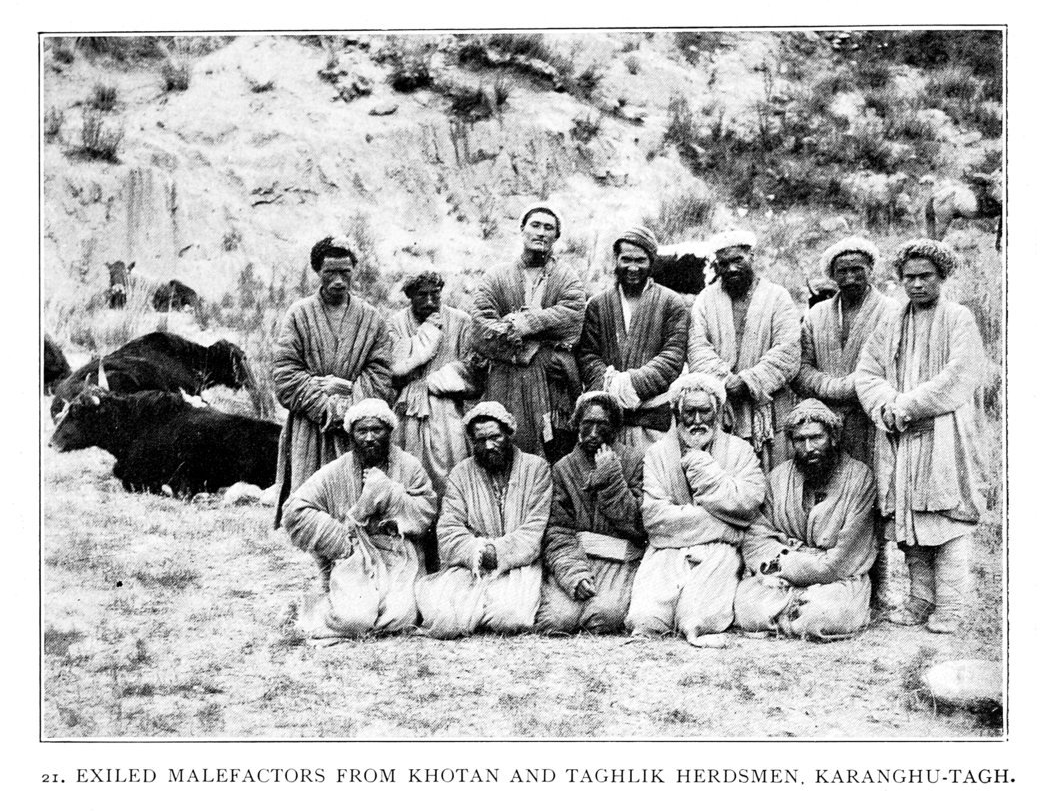

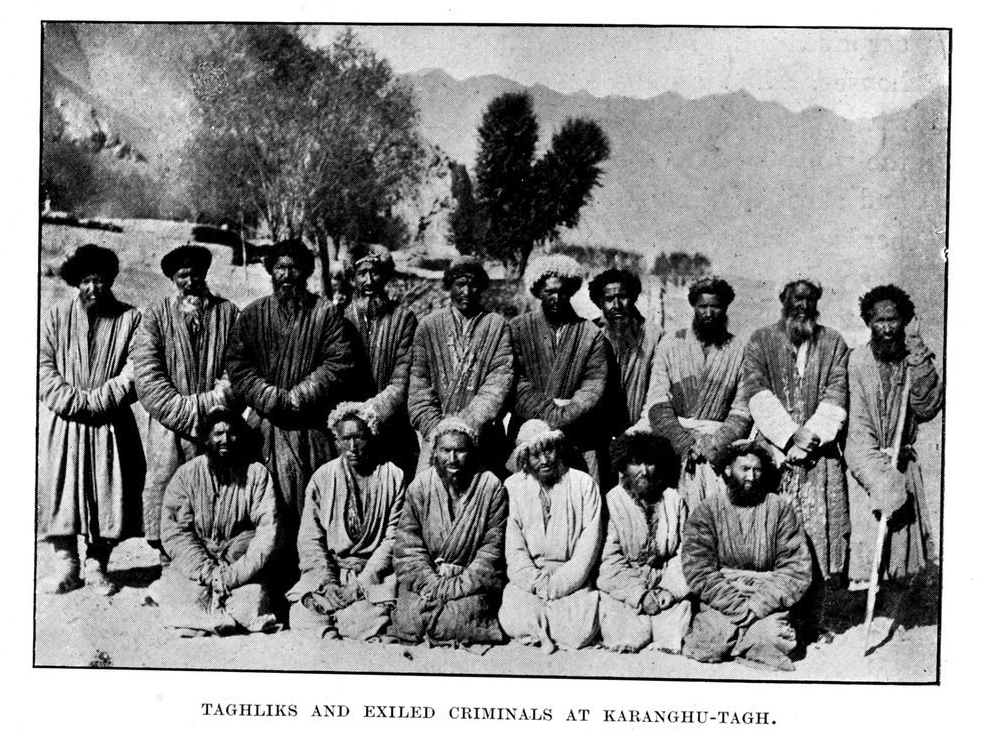

Kárangoták: Village of about 500 houses, which are chiefly occupied by convicts and exiles from the cities of Káshgár, Yárkand and Khotan. The road for the first portion is very rocky, lying down the Brinjgá River. Poplars and other trees are very numerous; cultivation is carried on, but not to a large extent. This place is situated on some flat ground on the right bank of a large mountain torrent which flows from a snowy ridge to the west, and is noted for the “yashm,” a description of agate stone, prized by the Chinese, and which is met with in the stream. The inhabitants of this village are particularly uncivil to travellers, and show disrespect even to the officials of the country. The convicts are known by their beards being kept shaved, and their faces branded with round marks.[1]

So, Qarangghu Tagh was a centre of jade production (yashm is Persian for jade), and it was a prison. Both of these things would be enough to put the village on the administrative map during the Qing, making it likely that Qing accounts of the village could also be found. Sticking with foreign travel accounts, though, the next visitor to pass through was the Hungarian-Englishman Aurel Stein. He visited Qarangghu Tagh on two of his expeditions through Xinjiang, the first in October 1900, and the second in August 1906. Earlier accounts such as Johnson’s had piqued Stein’s interest in the region. Heading south from Khotan, he hoped to locate the source of the Yürüngqash River, and trace the old route through to Ladakh.

Stein liked to take his travel advice from medieval accounts such as those of Marco Polo and Xuanzang, and for his report on his first expedition (Ancient Hotan), he dug up references to Qarangghu Tagh from Islamic sources. In the Zafarnama, a history of Tamerlane’s conquests written in the fifteenth century, Sharaf al-Din ʿAli Yazdi mentions Qarangghu Tagh as “a very steep and rugged mountain, to which the inhabitants of Khotan and the neighbouring places fly for refuge in time of war.” Mirza Haydar also mentions the village in the Tarikh-i Rashidi (written in the 1540s), while narrating the flight of his uncle Mirza Ababakr from Yarkand. Ababakr had just lost out in a struggle for the throne with Saʿid Khan of the Chaghatayid Moghul dynasty. Like so many similar accounts of aristocratic escapees, Mirza Haydar describes his relative gradually divesting himself of his wealth on the way through Qarangghu Tagh. Here is Wheeler Thackston’s translation:

Mirza Ababakr went to Khotan and from there to Qaranghu Tagh. Hard on his heels came news of a Mogul posse in pursuit. The roads were narrow. It was impossible to carry all those possessions, so he piled up all his textiles and baggage, gold and silver utensils and set fire to them, burning a king’s ransom to ashes in a moment. The jewel-studded ornaments he put in saddlebags full of gold dust and cast them from the bridge over the Aq Tash River, which flows through Qaranghu Tagh. He killed his thoroughbred horses and pack camels and went on his way, taking what he could to Tibet.[2]

On his first visit to Qarangghu Tagh in October 1900, Aurel Stein found it a place of considerable foreboding, and he rendered the village’s name, with poetic license, as “The Mountain of Blinding Darkness.” The local village head, the yüzbashi, was not inclined to help Stein with his onward journey, but Stein was carrying the seal of the Chinese amban in Khotan, and he bullied the yüzbashi into submission. The next morning he was able to obtain the supplies he needed. This, he writes,

…was no difficult task, for Karanghu-tagh, though hidden away amid a wilderness of barren mountains, is a place of some resources. When I inspected it in the morning I was surprised to find a regular village of some forty closely packed houses. The scanty fields of oats below and above could scarcely support this population. But Karanghu-tagh is also the winter station for the herdsmen who graze flocks of yaks and sheep in the valleys of the Upper Yurung-kash. These herds belong mostly to Khotan ‘Bais,’ or merchants, and the visits of the latter seem the only tie that connects this strangely forlorn community with the outer world. From time to time, however, Karanghu-tagh receives a permanent addition to its population in the persons of select malefactors from Khotan, who are sent here for banishment.

It would indeed be difficult to find a bleaker place of exile. A narrow valley shut in between absolutely bare and precipitous ranges, without even a view of the snowy peaks, must appear like a prison to those who come from outside. It was strange to hear the hill-men, who during the summer lead a solitary life in the distant glens, speak of Karanghu-tagh as their ‘Shahr’ or “town.” For these hardy sons of the mountains this cluster of mud-hovels, with its few willows and poplars, represents, no doubt, an enviable residence. To me the strange penal settlement somehow appeared far more lonely and depressing than the absolute solitude of the mountains.[3]

Before moving on, Stein toured the local burial ground, which features prominently in Saipulla’s film as the resting place of the massacred townsfolk. Stein also took some photographs of the denizens of Qarangghu Tagh on his way through (he calls the locals “Taghliks,” which just means “mountain-men”).

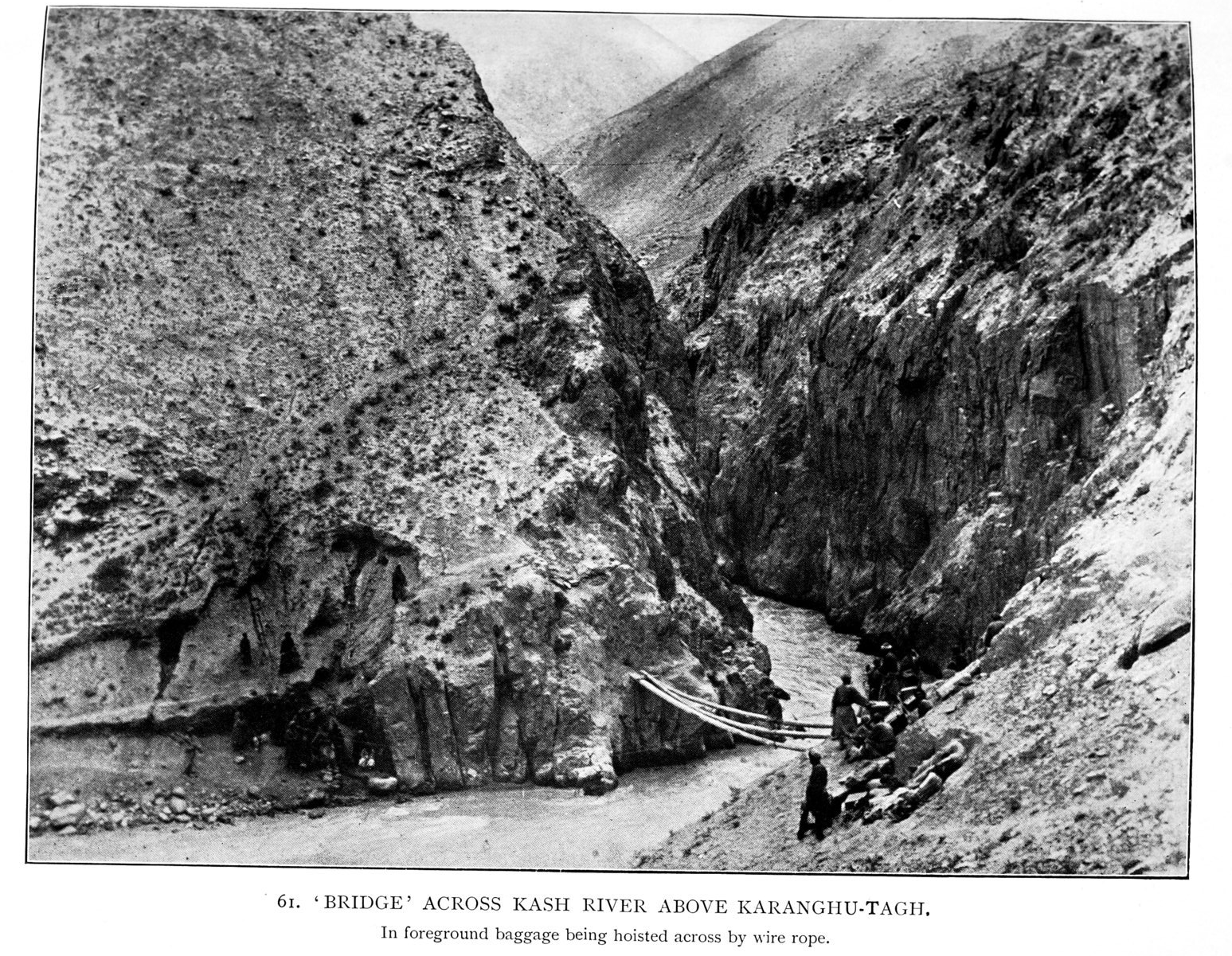

The shot below gives some idea of the almost impassable terrain heading in and out of Qarangghu Tagh, which we experience on motorbike in the opening scenes of Saipulla’s film.

These descriptions of Qaranggu Tagh I think help to explain why it might have become a scene of bloodshed during the Dungan occupation. As early as the fifteenth century, Yazdi had heard of it as a place where people “fly for refuge in time of war.” And with a population consisting of convicts and high-mountain herdsmen, it must have been a fairly lawless place through the Qing. Johnson found that its inhabitants “show disrespect even to the officials of the country.” Yet it was also a source of wealth, “a place of some resources” as Stein says. Apart from jade, which occurs naturally in the rivers, there is also gold in the vicinity of Qarangghu Tagh. In the 1930s, securing such wealth was essential for the large fighting force that the leaders of Tunganistan sought to maintain. On his way through Khotan in 1935, Peter Fleming could clearly sense that “the Turkis were groaning under the weight of other people’s military ambitions.”[4]

The mountains to the south of Khotan had already been a scene of political mobilization by the time the Dungans arrived on the scene. In 1933, a rebellion broke out among the gold-mining community of nearby Qaraqash, an uprising that ultimately fed into the formation of the East Turkistan Republic in Kashgar. During Ma Hushan’s reign, there were Uyghur rebellions elsewhere in Tunganistan, and the mountains would have naturally provided the best refuge for those who felt the need to flee. Whether its inhabitants were engaged in active resistance, therefore, or simply hoping to use the inhospitable terrain to avoid the oppressive requisitions of the Dungan army, it’s not hard to see how Qarangghu Tagh might have become the target of a punitive expedition. Mountains can be a good place to hide, but you can also commit atrocities there without anyone noticing.

Maybe there’s more to know about this episode, and maybe there isn’t. For the locals, it’s already more the stuff of legend than active historical investigation. And Saipulla doesn’t press them for details either. While respecting the seriousness of the event, he has a very light touch as director, and is happy to let his interviews go in whichever direction they lead. The film’s actually very humorous, and at certain points the elderly villagers completely steal the show.

As I’ve already said, films like this don’t come along very often. Apart from Saipulla himself, producer Jessica Yeung at Hong Kong Baptist University also deserves congratulations for getting the film through editing and out into the world. Hopefully Qarangghu Tagh will eventually get the screen time it deserves, and make itself known beyond our circle of Inner Asia scholars and Chinese independent documentary fans. It’s not easy to make documentary films in Xinjiang these days, but I’m sure that Saipulla Mutallip will continue to produce interesting work wherever he finds himself.

References

[1] W. H. Johnson, “Report on his Journey to Ilchí, the Capital of Khotan, in Chinese Tartary,” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 37 (1867): 1-47.

[2] Mīrzā Ḥaydar, Mirza Haydar Dughlat’s Tarikh-i Rashidi: A History of the Khans of Moghulistan, translated by W. M. Thackston (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, 1996), 204.

[3] Aurel Stein, Sand-Buried Ruins of Khotan: Personal Narrative of a Journey of Archaeological and Geographical Exploration in Chinese Turkestan (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1904), 198-199.

[4] Cited in Andrew D. W. Forbes, Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 131.